Those who floated in the ark were weightless and had weightless thoughts. They were neither hungry nor satisfied. They had no happiness and no fear of losing it. Their heads were not filled with petty official calculations, intrigues, promotions, and their shoulders were not burdened with concerns about housing, fuel, bread, and clothes for the children. Love, which from time immemorial has been the delight and the torment of humanity, was powerless to communicate to them its thrill or its agony. Their prison terms were so long that no one even thought of the time when he would go out into freedom. Men with exceptional Intellect, education, and experience, but too devoted to their families to have much of themselves left over for their friends, here belonged only to friends.

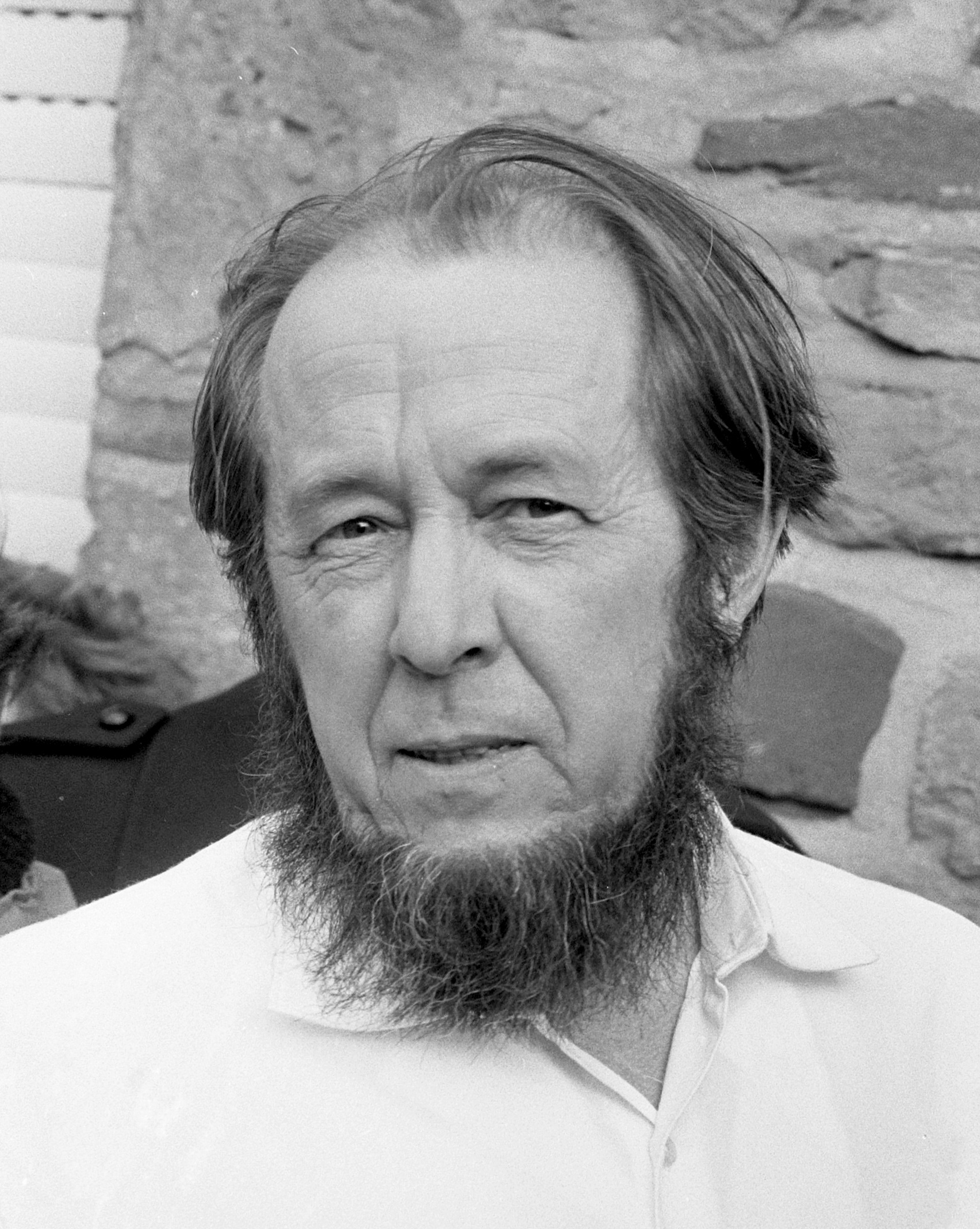

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

Related Quotes

I had a chance to read

Monte Christo

in prison once, too, but not to the end. I observed that while Dumas tries to create a feeling of horror, he portrays the Château d'If as a rather benevolent prison. Not to mention his missing such nice details as the carrying of the latrine bucket from the cell daily, about which Dumas with the ignorance of a free person says nothing. You can figure out why Dantès could escape. For years no one searched the cell, whereas cells are supposed to be searched every week. So the tunnel was not discovered. And then they never changed the guard detail, whereas experience tells us that guards should be changed every two hours so one can check on the other. At the Château d'If they didn't enter the cells and look around for days at a time. They didn't even have any peepholes, so d'If wasn't a prison at all, it was a seaside resort. They even left a metal bowl in the cell, with which Dantès could dig through the floor. Then, finally, they trustingly sewed a dead man up in a bag without burning his flesh with a red-hot iron in the morgue and without running him through with a bayonet at the guardhouse. Dumas ought to have tightened up his premises instead of darkening the atmosphere.

— Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

1968book-reviewcount-of-monte-cristo

By apeculiar coincidence, the very day when I was giving my address in Washington, Mikhail Suslov was talking with your senators in the Kremlin. And he said, "In fact the significance of our trade is more political than economic. We can get along without your trade." That is a lie. The whole existence of our slaveowners from beginning to end relies on Western economic assistance....The Soviet economy has an extremely low level of efficiency. What is done here by a few people, by a few machines, in our country takes tremendous crowds of workers and enormous amounts of material. Therefore, the Soviet economy cannot deal with every problem at once: war, space (which is part of the war effort), heavy industry, light industry, and at the same time feed and clothe its own population. The forces of the entire Soviet economy are concentrated on war, where you don't help them. But everything lacking, everything needed to fill the gaps, everything necessary to free the people, or for other types of industry, they get from you. So indirectly you are helping their military preparations. You are helping the Soviet police state.

— Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

communismefficiencypolice-state